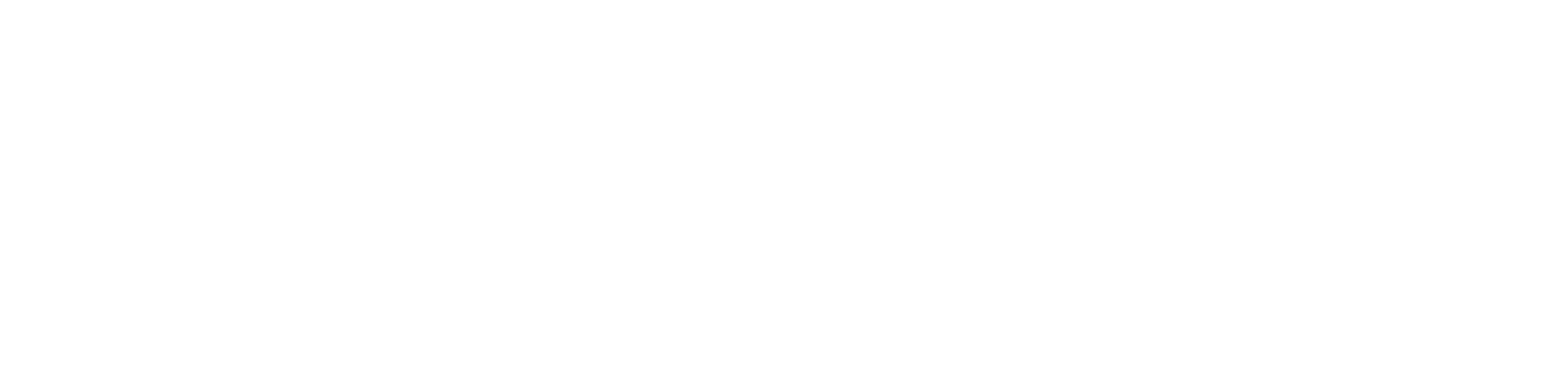

A talk with director Ekiem Barbier and producer Boris Garavini

*Transcribed from an audio interview with Ekiem Barbier and Boris Garavini

(Български превод по-долу.)

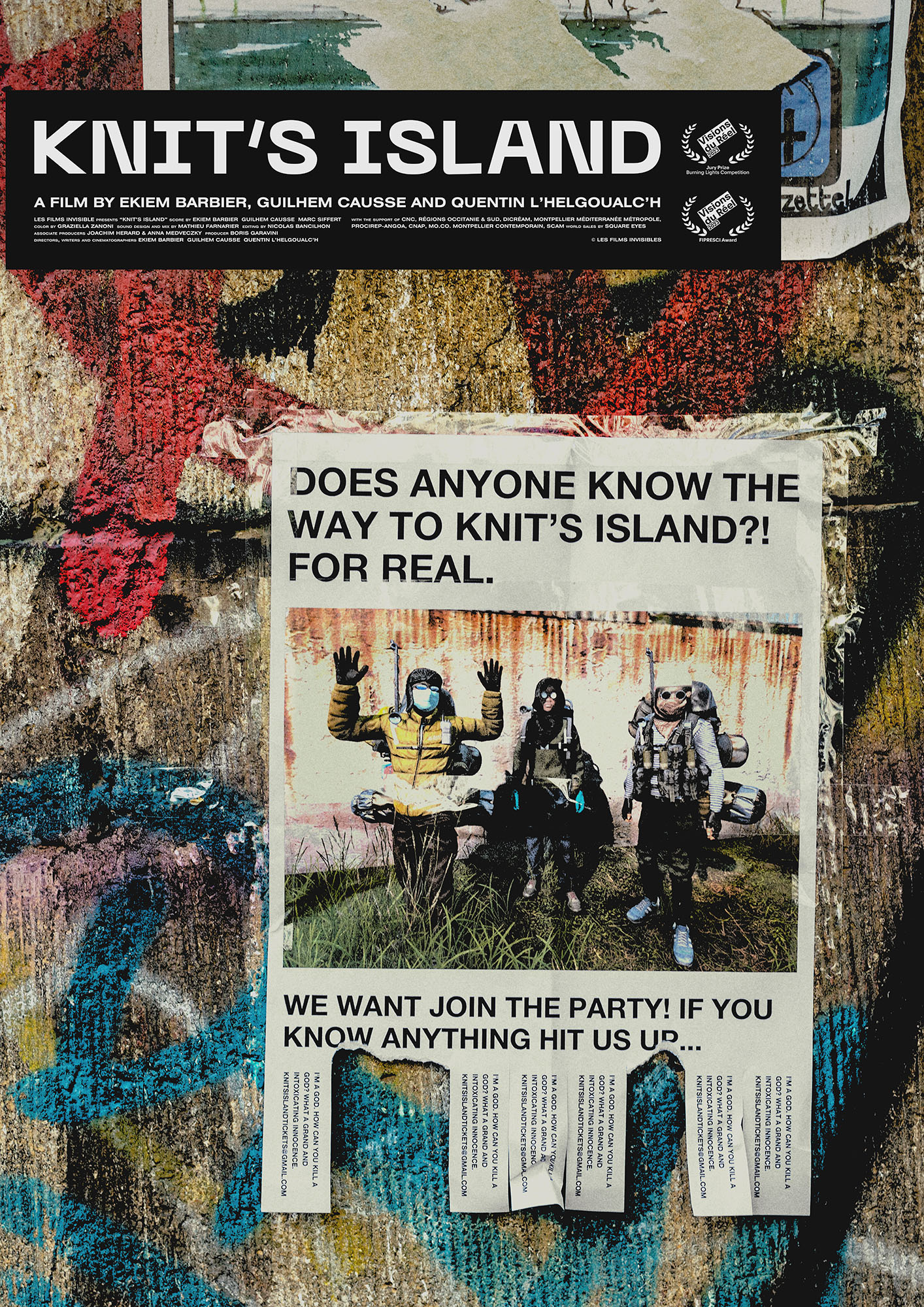

Doni Georgiev: As far I know, your intention with Knit’s Island was to make a documentary film in the already fictional reality of video game. You are filming in a role-playing videogame which makes it particularly interesting as there is a significant performative element in the gameplay. How did you become part of this virtual community and manage to make some players slip out of their role and reveal parts of them?

Ekiem Barbier: We actually decided to consider this entire world of gaming and the particular servers we decided to shoot in as real places in order to consider it as real as possible. We met together in a house and had a huge setup, and we were practically in an artificial lockdown, actually, for the first step of the shooting. And we were together and deciding day to day what we were shooting and there were a lot of weeks and months of research before that, and so we decided to meet the people inside the game exclusively. That meant that we had to handle the game, its mechanics and all of it to be able to be at the same level as the players. From that, we managed to meet people inside the game, completely randomly during a walk in the forest. We suddenly met someone and and he was asking for water, and we needed food. We exchanged those goods, we had a barbeque in the forest, and then we talked about our project. You also have to know that in those kind of games roleplay is important, but what’s the most important is the trust you put in two people. If you meet someone and it’s going to ruin your four hours gameplay obviously, you have to trust those people, and in order to trust them, you have to grab some clues that they are, let’s say, good people in away. That’s entirely subjective. It’s your opinion and your instinct decides for those things. At some point, we managed to meet people, to keep contact and to play and be with them for a long time. When you talk with someone in an online server, someone you don’t know, you’ve never seen before, and you have like an hour conversation about their life here as players and stuff, they automatically begin to cross the border and talk about their real self.

D.G: Throughout the film, there’s somewhat of a tension between loneliness and connection. How did you approach and work with these opposing feelings throughout the process of making the film, especially in a virtual world?

E.B: The relationship between loneliness and connection is something inherent to virtual places and games like this. There are not opposite feelings in the game. It’s the whole point, I would say. Some people are playing alone at this game. What they are searching for is some kind of isolation through their own adventure. They can only rely to themselves and maybe they feel good that way. But most of the people try to engage in a conversation, to have interactions and maybe they have the chance to experience this in a longer period of time. They want to meet people, they want to be involved in a community and share some values, even if they are fictional or not. They want to be part of something. As a filmmaking team, we were already a team. The point was to invent our own gameplay or roleplay for the film. I wouldn’t say there is a tension between connection and loneliness. I would say it’s the same thing here. You are alone, but your purpose is to connect with everybody.

D.G: What drew you to the world of online survivalist role-playing games, and how did your perspective on virtual communities evolve during the filming process?

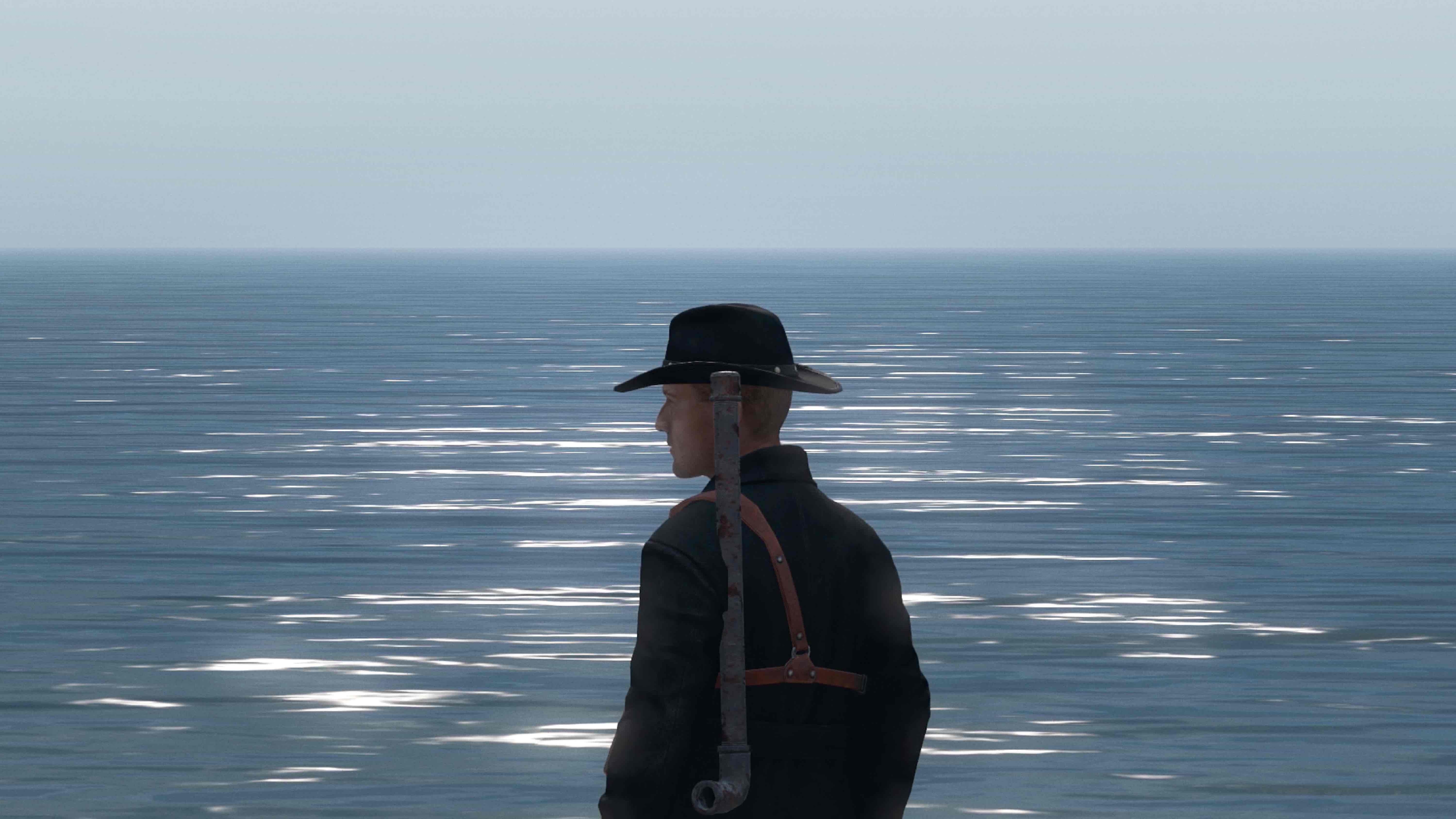

E.B: I would say first that there are not that many games like that where you can actually interact with other people, talk via a microphone and have the lips moving and have kind of a cinematographic environment. Those games are really few and were really few at the time when we begin the shooting (2019). We searched for it, we experienced maybe 4 or 5 games just to explore them and know if that was our best shot and DayZ quickly appeared like a place where everything was possible for us in terms of shooting. We were looking at it on YouTube and Twitch and what the people were doing. We noticed that people, because the game was a kind of an old game already, it had been going for maybe 7 or 8 years going, the people already had communities, they had created strong bonds. There were already stories and that’s what we were looking for, like a really involved community in the game, serious people playing, people that were connected together and have already created stories and have had a past together so then they can tell us the story.

The survivalist aspect of the game was really interesting for us because it’s about what people are picturing for the future - their hopes and their fears. We wanted to bring these subjects into the film as well. It’s also a game, a survival game. Survival games are places where people try to invent new forms of society. It’s a kind of a step back regarding to huge industrial and capitalistic enhancement of society. It’s like a step forward from that because there is no internet in the game. You can’t have money and buy stuff. You have to find new path, new ways to interact and make society. We were really interested in that. At first we thought that maybe everybody wanted to play the criminal, the cannibal, the horror stuff. But we knew and we discovered at the first steps of the shooting that it wasn’t the case. Many people were playing other kinds of roles too. We also dragged the people to our project.

Разговор с режисьора Екием Барбие и продуцента Борис Гаравини

Дони Георгиев: Доколкото знам, намерението ви с „Knit’s Island“ е било да направите документален филм във вече измислената реалност на видеоиграта. Снимате в ролева видеоигра, което я прави особено интересна, тъй като в играта има значителен перформативен елемент. Как станахте част от тази виртуална общност и успяхте да накарате някои играчи да излязат от ролята си и да разкрият части от себе си?

Екием Барбие: Всъщност решихме да разглеждаме целия свят на игрите и конкретните сървъри, на които решихме да снимаме, като реални места, за да ги възприемаме като възможно най-реални. Срещнахме се в една къща и имахме огромна техника, и всъщност бяхме практически в изкуствено затваряне за първата фаза на снимането. Бяхме заедно и всеки ден решавахме какво да снимаме, а преди това имаше много седмици и месеци на проучвания, така че решихме да се срещаме изключително с хората вътре в играта. Това означаваше, че трябваше да се справим с играта, нейната механика и всичко останало, за да можем да бъдем на същото ниво като играчите. Оттам успяхме да се срещнем с хора от играта, напълно случайно, по време на разходка в гората. Изведнъж срещнахме някого и той ни помоли за вода, а ние се нуждаехме от храна. Разменихме тези стоки, направихме барбекю в гората и после говорихме за нашия проект. Трябва да знаете, че в такива игри ролевата игра е важна, но най-важното е доверието, което имате в двама души. Ако срещнете някого и това очевидно ще ви развали четири часа игра, трябва да се доверите на тези хора, а за да им се доверите, трябва да хванете някои индикации, че те са, да речем, добри хора. Това е изцяло субективно. Това е вашето мнение и инстинктът ви решава тези неща. В даден момент успяхме да срещнем хора, да поддържаме контакт и да играем и да бъдем с тях дълго време. Когато говорите с някого в онлайн сървър, някой, когото не познавате, когото никога не сте виждали преди, и имате около час разговор за живота им тук като играчи и други неща, те автоматично започват да преминават границата и да говорят за истинската си същност.

Д.Г.: През целия филм се усеща известно напрежение между самотата и връзката. Как подходихте и работихте с тези противоположни чувства по време на процеса на създаване на филма, особено във виртуалния свят?

Е.Б.: Връзката между самотата и взаимоотношенията е нещо присъщо на виртуалните места и игри като тази. В играта няма противоположни чувства. Бих казал, че това е цялата идея. Някои хора играят тази игра сами. Това, което търсят, е някаква изолация чрез собственото си приключение. Те могат да разчитат само на себе си и може би се чувстват добре по този начин. Но повечето хора се опитват да влязат в разговор, да имат взаимодействия и може би имат шанса да изпитат това за по-дълъг период от време. Те искат да се срещат с хора, искат да бъдат част от общност и да споделят някои ценности, дори и да са измислени. Искат да бъдат част от нещо. Като екип от филмови продуценти, ние вече бяхме едно цяло. Целта беше да измислим наша собствена игра или ролева игра за филма. Не бих казал, че има напрежение между връзката и самотата. Бих казал, че тук е същото. Ти си сам, но целта ти е да се свържеш с всички.

Д.Г.: Какво те привлече към света на онлайн ролевите игри за оцеляване и как се промени гледната ти точка за виртуалните общности по време на снимачния процес?

Е.Б: Първо бих казал, че няма много игри от този тип, в които можеш да взаимодействаш с други хора, да говориш през микрофон, устните ти да се движат и да имаш нещо като кинематографична среда. Такива игри са наистина малко и бяха много малко по времето, когато започнахме да снимаме (2019 г.). Търсихме такива игри, изпробвахме може би 4 или 5, за да ги проучим и да разберем дали това е най-добрият ни шанс, и DayZ бързо се оказа място, където всичко беше възможно за нас по отношение на снимането. Гледахме я в YouTube и Twitch и наблюдавахме какво правят хората. Забелязахме, че хората, тъй като играта вече беше доста стара, съществуваше от около 7 или 8 години, вече имаха общности, бяха създали силни връзки. Вече имаше истории и това беше точно това, което търсехме – наистина ангажирана общност в играта, сериозни хора, които играят, хора, които са свързани помежду си и вече са създали истории и имат общо минало, за да могат да ни разкажат историята.

Аспектът на оцеляването в играта беше наистина интересен за нас, защото става дума за това, което хората си представят за бъдещето – техните надежди и страхове. Искахме да включим тези теми и във филма. Това също е игра, игра на оцеляване. Игрите за оцеляване са места, където хората се опитват да измислят нови форми на общество. Това е нещо като крачка назад по отношение на огромното индустриално и капиталистическо развитие на обществото. Но всъщност е крачка напред, защото в играта няма интернет. Не можеш да имаш пари и да купуваш неща. Трябва да намериш нов път, нови начини за взаимодействие и да създадеш общество. Това ни интересуваше много. Първоначално си помислихме, че може би всички искат да играят престъпници, канибали, ужасяващи неща. Но разбрахме и открихме още в началото на снимките, че не е така. Много хора играеха и други роли. Ние също привлякохме хората към нашия проект.

Бяхме като среща на общност. Понякога те бяха лидери или нещо подобно, а ние разговаряхме с тях и виждахме дали можем да стигнем до някакво споразумение. Можем ли да дойдем да снимаме за ден-два? Следващата седмица. И те приемаха, а ние продължавахме да снимаме с хората, които ни приемаха. Хората, които виждате във филма, не са представителни за всички участници в Daisy и други игри, всъщност те са доста специфични и уникални.

Д.Г.: Сътрудничеството изглежда от съществено значение в проект, който пресича реалния и виртуалния свят. Как тримата се справихте с творческите различия и поддържахте единна визия?

E.B: Мисля, че вече отговорих донякъде на този въпрос. Филмът е и за приятелството и сътрудничеството, за способността да правим неща заедно, да създадем обща платформа на реалността, обща история. Очевидно за нас тримата беше предизвикателство да направим филм. Това беше наш проект. Понякога го свързвахме с усилията, които хората полагат в играта, за да се съберат и да създадат нещо, защото е наистина трудно, дори и да играеш. Но когато снимаш филм, е доста трудно, защото имаш зомбита, болести, можеш да се разболееш, ако не почистиш водата и храната си, може да се простудиш и има толкова много неща.

В крайна сметка дори изядох собствените си партньори Гийем и Кентен по време на войната, защото бяха болни и умираха, а аз трябваше да продължа да пренасям някои предмети и материали на друго място за снимането. В крайна сметка ги изядох в играта, за да мога да оцелея и да продължа да правя филма. Това беше наистина екипен проект от началото до края. Това е същността на киното, то е екипна работа. Става въпрос да накараш някои хора да гледат в една и съща посока по едно и също време. Става въпрос да се изгради тази платформа на реалността, на общата реалност, за която говорих по-рано. За целите на филма ние се насочихме в различни посоки по отношение на техниките в киното. Кентен беше нашият главен оператор, така че той снимаше всичко. И той наистина се обучи да прави това във видеоигра. Гийем беше много добър технически с компютрите, компютърните проблеми и самата игра. Той ни носеше храна и ни поддържаше живи по време на снимките. Аз поех пътя на комуникацията с хората. Говорех с всички, поддържах връзка, задавах въпроси и понякога организирах снимките с хората. Ние си разделихме тази работа и я разделихме на няколко части до монтажа, музиката, всички тези неща.

Това е нещо като домашен филм. Практически направихме всичко и работихме с други хора по монтажа на звука и монтажа, хора, които не бяха там по време на снимането и които изобщо не се занимаваха с видеоигри. Имахме много взаимодействия и партньорства с много хора, включително нашия продуцент Борис, по време на снимането, писането, монтажа, всички етапи от създаването на филма.

Д.Г.: И един въпрос към продуцента на филма, Борис Гаравини. Филмът съчетава кино, технологии и култура на видеоигрите по начин, който предизвиква традиционните модели на производство. От гледна точка на продуцента, как се адаптирахте, за да подкрепите такъв неконвенционален проект – както творчески, така и логистично?

Борис Гаравини: Благодаря ви за това. Много ми е приятно, че ми задавате този въпрос, защото обикновено хората не питат какво мислят продуцентите. Продуцирането на такъв филм не е толкова различно, защото когато започнете да продуцирате този обект, трябва да признаете факта и да сте сигурни защо бихте третирали този обект по различен начин от всеки друг филм? Това е истински документален филм, който използва пряка кинематографична гледна точка, да речем кинематографична техника, начин за възприемане на реалността. За нас, за мен, това беше отправната точка на продукцията, че не трябва да го разглеждаме като различен от всеки друг филм, защото е филм, който ти позволява да се срещнеш с хора, да ги опознаеш, който има уникална и оригинална гледна точка по конкретна тема. Теоретично не виждам защо трябва да е различен. Разбира се, когато започнеш да работиш, осъзнаваш, че хората са склонни да имат предразсъдъци към игрите и света на игрите като цяло. Ще бъде трудно да се финансира, защото хората очакват, имам предвид, някои хора очакват от теб да излезеш с категорична гледна точка и с вече готово решение за това, с което трябва да се сблъскаме, когато влезем в този свят. Какво имам предвид? Говорейки за предразсъдъци, разбира се, знаеш какво искам да кажа. Хората мислят, че видеоигрите те правят агресивен, и разни такива неща от сорта.

Това са предразсъдъците и идеите, с които трябва да се сблъскаме. В този смисъл трябва да се работи много върху текста и намеренията, за да се накарат хората да разберат, че това е ценна тема, която заслужава да бъде проучена. Досега не е правено много по този въпрос. Трябва да се работи още по-усилено, когато става въпрос за досието. А досието, разбира се, се пише в сътрудничество с автора, от продуцента. Има много работа. На първо място, бих казал, че са необходими 1 или 2 години, за да се убедят комисиите и хората, които отпускат субсидии за подкрепа на такъв филм. Във Франция имаме късмета да разполагаме с доста функционална система, бих казал, що се отнася до нови начини на разказване и представяне на истории. Обърнахме се към феновете на творческите документални филми в CNC, Министерството на културата, регионалните фондове и хората бяха доста привлечени от това предложение, бих казал. Млади режисьори, които опитват нов подход, разбира се, това е нещо, което работи, донякъде. Въпреки че ни беше много по-трудно да убедим телевизионна мрежа или дистрибутор да се включат. Опитахме се да се свържем с Arte, France Television и други за тези слотове, но, разбира се, това беше първият ни игрален филм. Бяхме малко млади и неопитни, а и подходът, документалният подход, може би не беше толкова убедителен.

Беше трудно. Трябваше да завършим филма предимно с публични средства. И трябваше да инвестираме малко пари. Бяхме достатъчно късметлии, когато намерихме първия човек, който наистина ни се довери, който ни даде доверието си. Това беше Уолтър Дженсън от Square Eyes. Щом имахме дистрибутор, той видя груба версия на окончателния монтаж и се включи. Той беше съгласен, така че беше лесно да намерим начин. Но преди това бяхме малко самотни, бих казал. Имам предвид, че получихме известна подкрепа, не мога да се оплача. Знаете, системата работи, ако успеете да намерите начин. Но трябва да работите усилено по портфолиото. Трябваше да подходим към темата като към всеки друг филм, но начинът, по който всъщност продуцирахме филма, беше супер неконвенционален, защото никой от нас не беше правил филм в играта преди и нямаше много прецеденти. Имам предвид, Крис Маркър беше направил нещо, имаме Харун Фароки, Ален Дела Негра. Но доколкото ми е известно, нямаше филм, заснет изцяло в игра. Документални филми, не фикция или машинима. От правна гледна точка нямах никого и нищо, с което да сравнявам идеите си и върху което да работя. Беше много трудно, защото никой не знаеше как да снима.

Никой не знаеше как да снима филм в играта и играта беше трудна. Изискваше много проучвания, много смърт, опит да се измисли нов кинематографичен език, снимане само от гледната точка на играча, за да се уважават играчите, без да се използва свободно движеща се камера. Това беше първата точка. Трябваше да измислим начин да снимаме играта, а след това да намерим начин да получим правата на играчите. От юридическа гледна точка беше много трудно, защото искаш правата на аватар и на някой, който всъщност не е тук, правата да използваш гласа и личността му. Това беше супер объркано. После разработчиците на играта, разбира се, беше огромен залог, защото обикновено разработчиците не дават такива права. Знаем това със сигурност, защото опитахме няколко пъти с GTA 5, компаниите Rockstar и Take-Two и разработчиците. Беше трудно. Bohemia бяха доста нерешителни. Това не е точната дума. Те не казаха „да“ от самото начало, така че опитахме с GTA 5, Take-Two казаха „не“, не можете да използвате нашата игра, за да направите филм. Тогава се обърнахме към друга игра, DayZ, която беше доста интересна и даваше надежда. Всъщност имахме късмет, че Take-Two казаха „не“, защото DayZ беше много по-уникална в известен смисъл. Когато се обърнахме към тях, те казаха „да, защо не“, но трябваше първо да видят филма. Или щяхме да направим филма и да чакаме „да“, евентуално „да“, което не е нещо, което обикновено се прави. Приехме залога. Поехме риска.

Чакахме пет години, за да получим одобрението им. В крайна сметка просто изпратихме грубия монтаж, супер изплашени, и те казаха „да, не е зле, просто махнете това, това и онова”. Бъговете изглеждат странни. Казахме “Това е част от артистичния процес. Искаме да запазим тези бъгове във филма. Знам, че показват играта не по начина, по който сте искали, но това е част от преживяването за играчите”. Трябваше да изложим някои аргументи. Трябваше да измислим силни аргументи. И накрая те казаха „да“. Бяхме доста късметлии, че приехме този залог. От правна гледна точка, от художествена гледна точка, каквото и да е, трябваше да измислим всичко. И това, разбира се, не беше никак обичайно. Въпреки че самият филм, за мен, е като всеки друг документален филм – излизаш в дивата природа, опитваш се да спечелиш доверието на героите. Прекарваш много време на място, на терен, приближаваш се до обекта си, опитваш се да спечелиш доверието му.

Д.Г.: Вашият филм може да се разглежда като форма на машинима – филм, създаден във видеоигра, използвайки нейния двигател. Какво е вашето мнение за машинима като жанр и как виждате неговото бъдеще, както в общ план, така и във връзка с професионалното кинопроизводство?

E.Б.: Всъщност това е интересен въпрос. Машинима е като техника. По принцип това е създаване на филми с кадри от видеоигри, но в повечето случаи не става въпрос за реалност. Повечето пъти е фикционално или се използва за създаване на музикални клипове или други неща, но има и някои филми, които са документални, като „Les Survivants” на Никола Байе. Имаме един от последните филми на Крис Маркър – „Ouvroir, the movie”, който е за неговата изложба, неговата собствена изложба в Second Life. Мисля, че постепенно се е превърнал в нещо много по-разнообразно и много хора използват кадри от видеоигри.

Това също е част от началото на нашия проект – да гледаме много видеоигри и кадри от видеоигри и да не можем да видим това в нашата реалност, сякаш е част от виртуален свят, който по някакъв начин ни се струва далечен. И искахме да върнем това в по-масовата култура. Можете да видите, че сега кадри от видеоигри се използват много в Twitch и YouTube. Много хора ги гледат на екрана, без да играят. Имам предвид, че хората просто гледат кадри и очевидно това ще се превърне в нещо огромно, предполагам, че за мен ще замести телевизията, телевизионните предавания. Хората гледат ролеви игри в GTA 5, например. Това е нещо като ново предаване, в което се появяват по-млади телевизионни звезди, а играта е доста популярна в целия свят, така че може да привлече огромна аудитория. Мисля, че това е част от бъдещето на това, което остава от телевизията.

За киното не знам, защото струва много време и пари, а повечето хора, които идват от гейминг обществото, бих казал, че нямат инструментите да го правят. Те просто правят видеоклипове и това, което наричат съдържание, в YouTube и други подобни, но мисля, че е бавен процес и ще отнеме време. Но наистина виждам как риалити шоута се поставят във виртуален свят. Всъщност това вече се случва. Видеоигрите са нещо като инструмент или средство за създаване на каквото пожелаете. Може да е изкуство, реклами или каквото и да е. Просто е средство, което можете да използвате, за да правите неща. Смятаме, че е спешно и необходимо да свършим работата, да отидем там и да видим какво се случва. Защото дори и да го считате за виртуално или нереално, не можете да игнорирате факта, че се случва и променя живота ни или начина ни на мислене. Смятаме, че сега е моментът да се опитаме да изградим тази платформа на реалността, тази обща реалност заедно с хората. Време е да се заемем с този материал като артисти в тези места и да се опитаме да говорим за това, защото е поетично и политически важно за нас.

Представянето на филма се осъществява с финансовата подкрепа на Европейския съюз – СледващоПоколениеЕС по инвестиция BG-RRP-11.016-0049 с управляващ орган Национален фонд „Култура“. Цялата отговорност за съдържанието се носи от авторите и при никакви обстоятелства не може да се приема, че този филм отразява официалното становище на Европейския съюз и Национален фонд „Култура“.

We were like a meeting community. Like sometimes they were a leader or some stuff, and we were talking to them and see if we can come to some sort of agreement. Can we come to shoot for a day or two? Next week. And they accept that and, and and we, we pursue our, our shooting with the people that accepted us also. It’s not like people you can see in the movie is not representative of all the, the, the, the players in, in Daisy and other games also, it’s quite particular and quite unique actually.

D.G: Collaboration seems essential in a project that crosses real and virtual worlds. How did the three of you navigate creative differences and maintain a unified vision?

E.B: I think I already maybe answered a bit to that question before. It’s also a film about friendship and collaboration and being able to do stuff together, to create a common platform of reality, a common story. Obviously, it was kind of a challenge for us, for the three of us to be able to make a film. It was our project. Sometimes, we kind of related this to the struggle that people had into the game to get together and make stuff, because it’s really difficult, even if you are playing. But when you are shooting the movie, it’s iquite difficult because you have the, the zombies, the illness, you can get sick if you don’t clean your water and food and you can get cold and there is so much stuff.

I even ended up eating my own partners Guilhem and Quentin during the war, because they were sick and dying, and I had to keep going to transport some objects and materials to another place for the shooting. I ended up eating them in the game so I can survive and continue making the film. It was really kind of a team project from the beginning to the end. It is what cinema is about, it’s a team thing. It’s about making some people look in the same direction at the same time. It’s building this platform of reality, of common reality I talked earlier. For the purpose of the film, we kind of directed ourselves into different directions regarding techniques in cinema. Quentin was our main cinematographer so he was filming the whole thing. And he really trained to do that in a video game. Guilhem was really good technically with the computers, computer issues and the game itself. He was bringing us food and maintaining us alive during the shooting. I took the path to communicating to the people. I was talking with everybody, staying in contact, asking the questions and sometimes organizing the shooting with the people. We kind of shared this amount of work and divided it in several parts until the editing, the music, all the stuff.

It’s kind of a homemade film. We did practically everything and we worked al with other people on the sound editing and editing, people that were not there at the shooting and that were not involved into video games at all. We had many interactions and partnerships with a lot of people, including our producer Boris, during the shooting, the writing, the editing, all the stages of filmmaking.

D.G: And one question for the producer of the film, Boris Garavini. Knit’s Island merges cinema, technology, and videogame culture in ways that challenge traditional production models. From a producer’s perspective, how did you adapt to support such an unconventional project — both creatively and logistically?

Boris Garavini: Thank you for that. It’s very nice being asked something because usually people don’t tend to to ask what producers think. Producing such a film it’s not that different because when you start to produce this object you have to acknowledge the fact and you have to be sure why would you treat this object differently than any other film? This is a proper documentary that uses a direct cinema point of view, let’s say cinema direct technique, a way of apprehending reality. For us, for me, that was the starting point of the production, that we should not consider this as different as any other film because it’s a film that allows you to encounter people, to get to know them, that has a singular and original point of view about a specific topic. I don’t see why it should be different, theoretically. Of course, when you start to work, you realize people tend to have prejudices toward games and gaming world in general. It’s going to be hard to finance because people expect, I mean, some people expect from you to come up with a definitive point of view and with an already pre-made answer about what we should face getting into this world. What do I mean? Talking about prejudices, of course, you know what I intend to say. People think video games make you violent, you know, stuff like that.

This is the kind of prejudices and ideas we have to face. In that sense, you need to work a lot on the text and the intentions to make people understand that this is a valuable topic to explore. It has not been done that much before. You have to work even harder when it comes to the dossier. And the dossier, of course, is being written in collaboration with the author, by the producer. There is a lot of work. At first, I would say 1 or 2 years to convince the committees and the people who give grants to support such a film. We are lucky enough in France to have a quite functional system, I would say, when it comes to new narrative and new way of imagining and telling stories. We went for those creative documentary fans in CNC, the Ministry of Culture, in the regional funds and people were quite attracted by this proposal, I would say. Young directors trying a new approach, of course, that it’s something that works, kind of. Though we had much more trouble to convince a network or a distributor to come on board. We tried to approach Arte, France Television, and others to those slots but, of course, it was the first feature film. We were a bit young and fresh and the treatment, the documentary treatment was maybe not that convincing as well.

It was hard. We had to finish the film mostly with public funds. And we had to invest a bit of money. We were lucky enough when we found the first person who actually trusted us, who gave us his trust. It was Wouter Jensen from Square Eyes. Once we had the distributor on board, he saw like a rough version of the final cut, and then he went on board. He was on, so it was easy to find a way. But before that we were a bit lonely, I would say. I mean, we got some support, I cannot complain. You know the system kind of works if you manage to find a way. But you need to work hard on the dossier. We had to approach the subject as any other film, but the way to actually produce the film and was super unconventional, because none of us had made a film in the game before and there were not many precedents. I mean, Chris Marker had done something, at the end of his life, and we have Harun Farocki, Alain Della Negra. But to my knowledge, there was no film entirely shot in a game. Documentary films, not fiction or machinima. On the legal point of view, I had no one and nothing as a comparison to base my ideas and work on. It was very hard because nobody knew how to shoot.

Nobody knew how to properly shoot a film in the game and the game was hard. It was a lot of scouting, a lot of death, trying to invent a new cinematic language, only shooting from the player’s point of view to respect the players, not to use a free roaming cam. That was the first point. We had to invent a way of filming the game, and then we had to find a way to get the rights of the players of the game. Juridically, it was very hard because you’re asking an avatar and someone who’s not really here, his right, the right to use his voice and his personality. That was super fucked up. Then the game developers, of course, it was a huge bet because usually the developers, they don’t grant rights like that. We know that for sure because we tried a few times with GTA five, Rockstar and Take-Two companies and developers. It was hard. Bohemia, they were quite reluctant. That’s not the word. They didn’t say yes in the very first place so we tried GTA five, Take-Two said, no, you cannot use our game to make a film. Then we went to this other game DayZ, it was quite interesting and hopeful. We were quite lucky, actually, that Take-Two said no, because DayZ was much more singular in a way. When we approached them, they said yeah, why not, but we should see the film first. It was either we would do the film and wait for a yes, an eventual yes, which was something you don’t do usually. We took the bet. We took the risk.

We’ve waited for five years to get their approval. In the end, we just sent the rough cut super freaked out, and they said, sure. It’s not bad. Just remove this, this and that. Bugs seem strange bugs. We said no, please. It’s part of the artistic process. We would like to keep those bugs in the film. I know they’re showing the game not in the way you intended to, but it’s part of the experience for the players. We had to show some arguments. We had to come up with strong arguments. And they said yes in the end. We were quite lucky that we took this bet. From a legal point of view, artistically, whatever, we had to invent everything. And that was, of course, not common at all. Although the film itself, to me, is like any other documentary, you go out in the wild, you try to gain characters confidence. You spend a lot of time on the ground, on the field, approaching your subject, trying to gain trust.

D.G: Your film can be seen as a form of machinima — a film created within a video game using its engine. What is your perspective on machinima as a genre, and how do you see its future, both in general and in relation to professional filmmaking?

E.B: It’s an interesting question, actually. Machinima is like a technique. It’s basically making movies with video game footage, but most of the time it’s not really about reality. It’s most of the time fictional or it is used to make some music clip or stuff, but there are some movies that are also documentary movies like “Les Survivants” de Nicolas Bailleul. We have one of the last films by Chris Marker – “Ouvroir, the movie” which is about his exhibition, his own exhibition in Second Life. I think it has slowly evolved into something much more diverse now and tons of people are using video game footage.

That’s also part of the beginning of our project, seeing video games and video games footage a lot and not being able to see that in our reality, like it was some part of a virtual world which was feeling distant in a way. And we wanted to bring that back into a more mainstream culture. You can see that now video game footage are used in Twitch and YouTube a lot. Tons of people are seeing this in on a screen and they are not playing. I mean people are just looking at the footage and it’s obviously gonna become something huge, I guess it’s going to replace TV for me, TV shows. People are watching role play on GTA 5, for instance. It’s kind of a new show where younger TV stars are appearing on this, and the game is quite popular worldwide that you can drag an immense amount audience for this. I think it’s part of the future of what remains of TV.

About cinema, I don’t know, because it costs a lot in terms of time and money and that most of the people that come from the gaming society, I would say don’t have the tools to do that. They just make videos and what they call content on YouTube and stuff, but I think it’s a slow process and it’s going to take time. But I’m really seeing like reality TV shows being placed in a virtual world. It’s already happening, actually. Video game is kind of a tool or a medium to create whatever you want. It might be art or ads or whatever. It’s just a medium you can use to do stuff. We think it’s kind of urgent and and necessary to do the job and go there and see what’s happening. Because even if you consider this as virtual or as not real, you can’t ignore that it’s happening and it’s modifying our lives or ways of thinking. We think that right now it’s really the time to try to build this reality platform, this common reality together with people. It’s the time to get our hands on this footage as artists in these places and try to talk about this because it’s poetically and politically important to us.

Представянето на филма „Островът на Нит“ и това интервю се осъществяват с финансовата подкрепа на Европейския съюз – СледващоПоколениеЕС по инвестиция BG-RRP-11.016-0049. Цялата отговорност за съдържанието се носи от авторите и при никакви обстоятелства не може да се приема, че този документ отразява официалното становище на Европейския съюз и Национален фонд „Култура“.